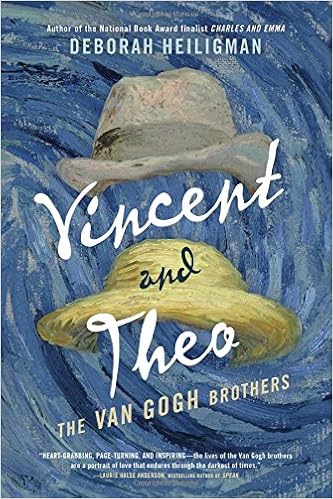

I’ve just – only just—finished reading Vincent and Theo: The Van Gogh Brothers by Deborah Heiligman. This

was urged upon me by Anita Silvey, whose recommendations one should never

overlook, speaking on the power of children’s and teen nonfiction to an

audience at Vermont College of the Fine Arts. I had just recently met Deborah

Heiligman, briefly, at the American Library Association Annual Conference in

Chicago, and her warmth and sincerity leaped across the room. Her masterful

work, a lovingly constructed narrative pieced together from the copious correspondence the Van Goghs share, does the same.

I’ve always loved Vincent Van Gogh (but who doesn’t?), but I

knew only the most superficial things about him. Dutch, painted in southern

France (a favorite place of mine), mentally ill, cut off his ear, committed

suicide. Somewhere I’d picked up the notion that he was a bit of a randy,

carousing fellow, but I’m not sure where – it may have been an episode of Dr.

Who. (See the starry Tardis, below.)

Heiligman writes, in her author’s note, that when she first

learned about Theo, on a visit to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, she wrote

the following in her notebook: “What does everyone remember about him? The ear,

killing himself. And some paintings, of course. But what about his religion and

his decision to become a painter so he could leave the world a souvenir?” She

goes on to say, “And then I wrote: ‘Story of brothers. (And sister-in-law.)’” (page

425).

Heiligman writes, in her author’s note, that when she first

learned about Theo, on a visit to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, she wrote

the following in her notebook: “What does everyone remember about him? The ear,

killing himself. And some paintings, of course. But what about his religion and

his decision to become a painter so he could leave the world a souvenir?” She

goes on to say, “And then I wrote: ‘Story of brothers. (And sister-in-law.)’” (page

425)..jpg/170px-Vincent_van_Gogh%2C_Portrait_of_Theo_van_Gogh_(1887).jpg) |

| Theo Van Gogh |

What do we always try to tell young people in our books?

That to know a person, to really observe a life, is to peel away stereotypes,

prejudices, gossip and slander, and get to the heart of earnest desires,

foolish errors, hopes and sorrows. We preach that we cannot judge another

until we really understand them. The secret, of course, is that whom we

understand, we hesitate to judge; whom we understand, we love; whom we love, we

ache and yearn for.

I’ve spent the last few days riveted by Vincent and Theo,

weeping at the sorrows they bore together, but weeping more at the beauty of

their bond. Theirs is a complex affection, sometimes turbulent, but always

loyal, and boundless in mutual compassion. Theo’s devotion to Vincent, his

support (financial and emotional), his unwavering belief in his brother’s

potential are an indictment in my own soul of the sister I am not, the wife I

am not, the mother I am not. (But this is not about me, so I’ll set my penchant

for confession aside.) I never knew about Theo at all, and because I didn’t, I

didn’t know about Vincent at all.

Those superficial labels I had acquired somewhere along the way

(messed-up, suicidal, rowdy) gave me no information about the fervor with which

Vincent approached art and life, and the agonies and ecstasies with which he

experienced both. If life is a radio signal, the receiver that was Vincent multiplied

wave amplitudes. Both joy and sorrow seem almost to have been too much for him.

He poured it onto canvas after canvas, and we are the beneficiaries. Canvas

after canvas, paint tube after paint tube, meal and rent and doctor’s bill,

were gifts to him (and therefore, the lucky world), given by Theo.

There’s so much more I’d like to say, about how Heiligman’s

work has revealed the warmth and generosity of Vincent’s heart, his eagerness

for connection, and his sweetness toward his friends and family (even when they hardly knew

what to do with him). I’m moved and rebuked by the purity of Theo’s affection,

by how quick he was to forgive and set offenses aside for the sake of intimate childhood

and brotherly love, how patient he was with trials Vincent could not control. Not resentfully, not dutifully, but wholeheartedly. Engrossed

as I was in the Van Goghs’ story, I couldn’t help connecting thread after

thread of it to my own life – to my experiences with siblings and as a mother

to four brothers; to my experiences observing acute mental illness in all its

terrifying force, and chronic mental illness in its eroding relentlessness. I’m

grateful to live in an age where there’s so much more we can do to help

sufferers, though there’s far more to be done. I can’t help comparing the

urgency and passion of Vincent’s approach to his art to my own relationship with my writing. I doubt Vincent ever got bored with his WIP, griped about his deadline, loitered around on CNN for a while, then paid a thirteenth visit to His

Friend the Fridge.

Vincent and Theo

will scoop up awards, and it should. The book itself is a thing of beauty,

organized like an art gallery, decorated throughout with Vincent’s art,

featuring color plates and a trove of back-matter scrupulously annotating

sources and providing further context. I’m

urging it upon my own sisters (artists themselves) and on anyone who will

listen. This is compelling, moving,

heart-expanding read.

Vincent and Theo by Deborah Heiligman was published April 18, 2017 by Godwin Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Sons. Also available as an audiobook from Dreamscape Media.

_-_The_Olive_Trees_(1889).jpg)