Sometimes you read a book and your soul splits in two. Half

is overcome with rapture at its beauty and perfection. The other half beats its

chest and tugs its hair, knowing that you will never produce something this

exquisite, this perfectly constructed, nor this wise, and this book has just

exposed you for the fraud you are.

Reading is a risky business.

One book that shreds me like soggy paper is Rebecca Stead’s When You Reach Me. This 2010 Newbery

Medal winner doesn’t need my gushing. If you’re reading this post, you’ve probably

read the book. In hopes of learning something, I’ll try to push past

reverential awe and describe what’s working. Maybe my hair-tugging half can get

over herself and inch her work closer to what her counterpart so admires.

Of the novel’s dozens of literary virtues, I’m emphasizing

three: 1. The sequence of revelations and twists, 2. Manipulation of timelines

and narrator awareness, and 3. A reusable economy of characters, moments, and

objects. And a bonus fourth, TBA.

Virtue Number One: An intricately constructed

sequence of revelations and twists. Certainly Reach Me is tightly plotted, but I’m talking about more than plot.

It’s not simply that intriguing events, causally connected, are strung together

as close beads. (In fact, some causalities are bewildering until the puzzle

becomes clearer toward the very end, and this is one of its strengths.) It’s

not that details and characters which seem insignificant turn out,

surprisingly, to be crucial (more on that below). Rather, it’s that the

unspooling thread of the story doesn’t simply alternate between resolving past

mysteries and introducing new ones; every new revelation is simultaneously an

answer and a new question, twisting and complicating the puzzle ever more

minutely, and ratcheting the tension of reader curiosity ever higher. The best

mystery novels traverse this path well, playing cat-and-mouse with readers who

love this game-like or puzzle-like quality which forms the intellectual half of

the reader’s engagement. (In Reach Me,

the emotional half saves most of its wallop for the end, after the puzzle begins

to fall into place.)

Virtue Number Two: A Deft and Complex Manipulation of

Timelines and Narrator Awareness

Virtue Number Two: A Deft and Complex Manipulation of

Timelines and Narrator Awareness (or, who can know what, when). It’s unavoidable

for a time-travel novel to have a complicated, looping, and abstract sequence

of events (and sequence of presenting them). But

Reach Me not only gets every single timing note right (IMHO, and so

few time travel novels do, IMHO), but it employs those timelines, time-loops,

and knowledge gaps to excellent dramatic effect, choosing the novel’s beginning

at precisely the right time: Miranda knows much; she has experienced most of

the story’s key events, and can look back on them retrospectively, consciously

piecing together their significance, and yet,

and yet, the final puzzle piece has not yet snapped into place. She

does not yet know all. The big reveal, organically and deservedly, is yet to

come. Readers may scarcely notice when the actual story starts (and how it

differs from when the narrative she relates starts).

We have many timelines to keep track of in any story, with

extra layers and twists in this one. For example, we must parse out each of the

following in Reach Me:

- The linear order in which events happened.

- The order in which they are presented to the reader.

- [Courtesy of time travel element]: The order in which past

or future events converged with the story’s main timeline, such as, when

visitors left or visited the story’s timeline and interfered with it, and when

and how that interference is presented as a deviation. (If we can stretch our

brains to accommodate this idea, and depending on whether there are infinite

time-loops and multiverses or not, which will vary according to the

quasi-physics of each story. Thankfully not, in this case.)

- The moment in which the narrative consciousness telling the

events begins their telling (where & when are they then? Young/old/alive/dead/after-the-fact/living-the-story/somewhere-in-the-middle/post-denouement/pre-denouement?)

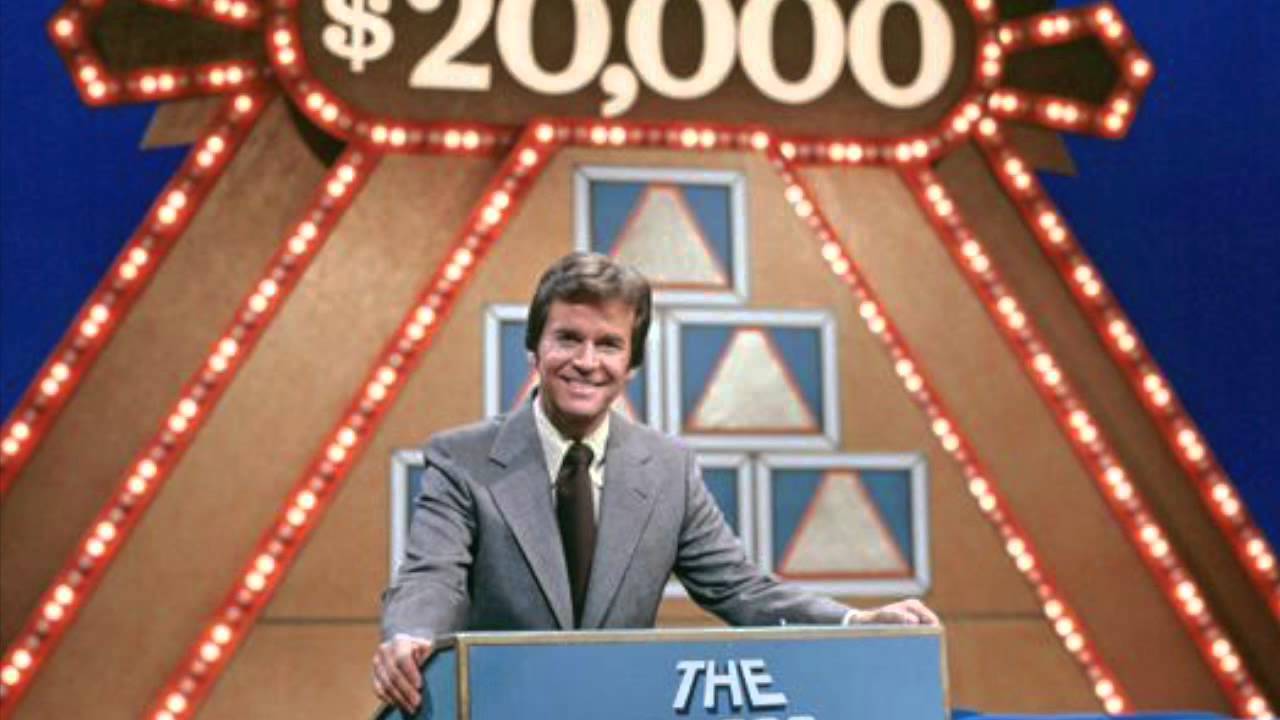

I don’t want to be too spoilery here, but consider the

significance of where Reach Me

begins: April 5 or 6, it seems: 21 or 22 days (if we allow Mom a day to steal a

calendar from her work supply closet) prior to Miranda’s mom appearing on The $20,000

Pyramid game show on April 27, 1979. The events of the story as Miranda

describes it began the prior autumn, beginning with her friend Sal getting

punched, and culminating in some pretty huge events in January. But the story

isn’t really and truly over until April 27, 1979, with some mop-up in the days

that followed. Or, perhaps, some 50-odd years later. Or, if Julia’s diamond

ring theory is correct, it’s never ended. It’s still happening now, and always

will be.

So when we read, we must keep a thumbnail placed in April,

1979, the

now of the narrative

consciousness, and of Miranda, who is both moving forward, quizzing her mom for the game show, and

looking backward; we must keep our other thumbnail in the sequence of past

events Miranda told us about which began last fall. Not only does this leaping

keep interest high, and deductive smoke puffing out of our ears, but it creates

many opportunities for sleight of hand, whilst Stead (or, I should say, the

narrative consciousness, see below) plants clue after clue, which we miss

because we’re stuck calculating the when of any given scene. Well played.

In

The Anatomy of Story, John Truby writes, “Withholding,

or hiding, information is crucial to the storyteller’s make-believe. It forces the

audience to figure out who the character is and what he is doing and so draws

the audience into the story. When the audience no longer has to figure out the

story, it ceases being an audience, and the story stops.” (page 7)

And again, on page 273, “A word of caution is warranted here.

Don’t overwrite exposition at the start of your story … The mass of information

actually pushes your audience away from your story. Instead, try withholding a

lot of information about your hero… The audience will guess that you are hiding

something and will literally come toward

your story. They think, ‘There’s something going on here, and I’m going to

figure out what it is.’” (emphasis added)

I’ll add an amen, but then my own caution: Withholding is

vital, but it demands a darn good reason for its secrecy. Readers expect to

unravel some knots, but they don’t like being manipulated. They expect fair

play. When details are withheld because the author is being coy or capricious,

for no good reason, or for stupid reasons (convenient amnesia that clears up

just in time, or a narrator just being a jerk), the reader feels betrayed. All

this is to say, Rebecca Stead’s manipulation of timelines, and of what could be

known when, creates a bulletproof justification for all of Miranda’s

withholdings. Even looking back on events as she was, there was so much she

didn’t understand. And the unusual story she had to tell, to a character who

would, in the future, fulfill events that were now already past, obligated her

to construct the narrative piece by piece, not alienating her special reader

(him) by revealing what she did

already know before the proper moment, when conclusions couldn’t be ignored or

rejected because they seem unfathomable and unbelievable.

Virtue Number Three: A Reusable Economy of Characters,

Moments, and Things.

Virtue Number Three: A Reusable Economy of Characters,

Moments, and Things. It’s very satisfying to readers when details, events,

things, and characters that would seem to be throwaway turn out to matter

later. (Up to a point.) It also creates a conveniently economical system for

the writer, who can thus keep the headcount, prop-count, and scene-count at

manageable levels. But it is a contrivance, and convenience can be carried too

far until believability suffers. The tidiness of fiction sometimes strays too

far from the randomness of reality. Here, however, the construct of the

Reach Me, as a letter, or rather, a

journal-like musing aimed toward a mysterious someone that feels letter-like,

written to a highly mysterious character, creates not just a reason but an

obligation for the narrator to be

selective in her presenting of details. She is entirely justified in revealing

only characters, details, and moments that will matter again later. To do

otherwise would be superfluous. From the outset, Miranda proposes to tell a

specific story, selecting only those events and people that are vital to it,

because she has a narrowly specific purpose in the telling, and has, in fact,

been given a mandate for the telling by the tell-ee (how bizarre! an intriguing

mystery in its own right), even though she constantly protests that mandate and

considers ignoring it (a choice that readers realize is perilous, whichever way

she chooses, even though there’s much that, as yet, we don’t understand). It’s

a virtuoso performance of manipulating the limitations of the narrative

consciousness of the novel to sophisticated heights. (The narrative

consciousness, or the mind behind the narration of any story, which is neither

its author, nor its protagonist/narrator, is something I’ve been jawing about

lately to anyone I can entrap into listening to me.) This unique setup of

telling a specific story to an unknown person, under protest, combined with the

time travel plot (not fully unzipped until the end) in which every detail she

relates is made to matter by the future person who will read the to-be-written

letter and treat it as instructions to be carried out, makes the revealed

significance and causal connectedness of each seemingly minor detail, thing,

person, and moment a triumph, rather than an eye-roll.

Bonus Virtue Number Four, which I could write 1000

words about, but I won’t: The many levels upon which this referential novel

explores

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine

L’Engle: as a beloved touchstone title; as a vehicle for book discussion and

debate, bringing people together; as a conduit for explorations that might change

the science of the future; as a catalyst for thematic discoveries relevant to

the story’s spiritual center. Lovely, lovely, worthy of this loveliest of

classics.

It’s the heart of a novel, and not its intellectual

sophistication, that moves readers to rapture and tears. Yet the masterfully

employed virtues of technique in When You

Reach Me build a rugged scaffolding for the real story, which is

beautifully simple, needing no tesseract, and played out on several plot lines

and pairings: People who have long cared about each other – or who learn to care about

each other -- can hurt each other

deeply; suffer sorrow, regret, and shame; and try, in bumbling but beautiful

ways, even after long interruptions, to make it right. Where there was love, there can be redemption,

and love can be found in the unlikeliest places.

I’m so glad this book

exists in the world.

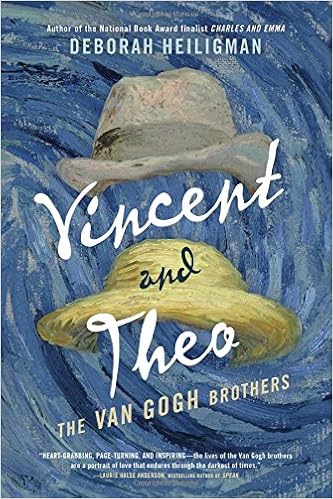

Heiligman writes, in her author’s note, that when she first

learned about Theo, on a visit to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, she wrote

the following in her notebook: “What does everyone remember about him? The ear,

killing himself. And some paintings, of course. But what about his religion and

his decision to become a painter so he could leave the world a souvenir?” She

goes on to say, “And then I wrote: ‘Story of brothers. (And sister-in-law.)’” (page

425).

Heiligman writes, in her author’s note, that when she first

learned about Theo, on a visit to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, she wrote

the following in her notebook: “What does everyone remember about him? The ear,

killing himself. And some paintings, of course. But what about his religion and

his decision to become a painter so he could leave the world a souvenir?” She

goes on to say, “And then I wrote: ‘Story of brothers. (And sister-in-law.)’” (page

425)..jpg/170px-Vincent_van_Gogh%2C_Portrait_of_Theo_van_Gogh_(1887).jpg)

_-_The_Olive_Trees_(1889).jpg)