This post is for some good friends of mine – fifth graders

at the schools I visit. Non-fifth graders – you may read it, too, if you like.

It’s time we talked about Point of View, or, as we call it

in the book world, POV.

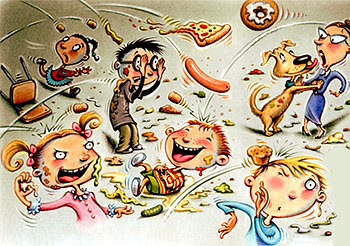

Imagine there’s a food fight going on in the school

cafeteria. What would you see? When you told your family about it, what would

you say?

|

| The Food Fight scene from "The Rat Brain Fiasco" by moi & Sally Gardner. Splurch Academy book 1. |

First of all, where were you when the fight broke out? And,

what role did you play in the fight? Were you:

- The kid who lobbed the first catapult of mashed potatoes with your spoon?

- The kid who fought back with a glop of slimy spaghetti?

- The kid who got the spaghetti in her face because kid #2 was such a bad shot?

- A kid at the next table over, yelling, “Food fight! Food fight!”

- A cafeteria monitor who hears the ruckus, sees flying sloppy joes and French fries, and thinks, “Not again!”?

- The assistant principal, in his office, who hears his crinkly walkie-talkie say, “Um, Mr. Martinez, we’ve got a situation in the caf?”

What you saw, what you did, and how you felt

about it would really depend on where you were when the fight broke out. Each

of the six people we listed above might go home and tell their families about

the fight in very different ways, even though they’re all talking about the

same fight.

When discussing stories, we often talk about a character’s point of view. What is it,

exactly?

Let’s look at those words closely. Point of view. The point from which you view

something. It’s the place (point) you’re standing while you watch (view)

something happen.

|

| Nurse Bilgewater and Professor Eelpot battle it out in "The Trouble With Squids." Splurch Academy book 4. |

Imagine this: Two sea monsters – a giant squid and a prehistoric-type sea serpent – are battling it out to the death in an ocean lagoon. Awesome, right? If you’re watching it, what do you see?

Well, that depends. Are you:

- Sitting on a cliff a hundred yards from the lagoon, watching something splash in the water?

- Standing on the beach, watching tentacles and a scaly tail heave up from the waves and crash down again with a terrific wet slap?

- Hovering over the lagoon in a helicopter, filming the whole thing with a news camera with a high-powered close-up lens?

- Trying to stay afloat in a little rowboat just a dozen or so yards away from this titanic battle, and nearly getting sucked into the undertow?

- The person who was swimming in the lagoon, when the sea serpent grabbed you, and opened his snapping jaws wide, when the squid appeared and snagged you with a tentacled arm to make you his own snack? Yikes!

The place where you were standing (or sitting, or flying,

or rowing, or swimming) would determine not only what you saw (viewed),

but also what you did, and what you felt. The guy on the cliff might wonder, “What’s

making that big splash?” But the swimmer in the water, about to become a

monster’s lunch, would be frantic to get away, and terrified every instant.

The term “point of view” uses sight (view) and position (point)

as metaphors for something that’s actually bigger than just what your eyes can

see, and from what distance. For one thing, you don’t just see a food fight or an ocean battle. You hear it – the squelching sounds and screaming school kids and

monster roars. You smell it – the scent of steamy ketchup, or the odor of a

gigantic fish. If your mouth was open, and a spoonful of chocolate pudding

landed IN your mouth, you’d taste the

food fight, too. (Gross. Someone else’s pudding!) You feel it – the plop of sloppy joe in your face, dripping down your favorite

shirt, or the splash of ocean spray in your face if you’re in the boat. Or

worse – the scrape and slime of cold tentacles and claws on your swimsuit-clad

body. Disgusting!

The term “point of view” uses sight (view) and position (point)

as metaphors for something that’s actually bigger than just what your eyes can

see, and from what distance. For one thing, you don’t just see a food fight or an ocean battle. You hear it – the squelching sounds and screaming school kids and

monster roars. You smell it – the scent of steamy ketchup, or the odor of a

gigantic fish. If your mouth was open, and a spoonful of chocolate pudding

landed IN your mouth, you’d taste the

food fight, too. (Gross. Someone else’s pudding!) You feel it – the plop of sloppy joe in your face, dripping down your favorite

shirt, or the splash of ocean spray in your face if you’re in the boat. Or

worse – the scrape and slime of cold tentacles and claws on your swimsuit-clad

body. Disgusting!

So “view” here stands for (or is a metaphor for) all of the

senses: seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching. But it goes farther than just

senses alone. POV/point of view takes into account who you are and what

your past experiences have been. Because, as we’ll see, who we are and what

we’ve gone through shape how we see things. For example:

- What if you’re the guy in the boat, and the girl in the clutches of the two sea monsters is your twin sister? How do you feel? Suddenly you’re not just trying to row your boat away. You’re trying rescue someone you love. Relationships affect POV.

- What if you’re the person in the helicopter with the video camera, and you’re a scientist, and you’ve spent your life saying there are still huge sea serpents in the ocean, and nobody has ever believed you? What if all your scientific colleagues have laughed in your face at marine biology conferences? And suddenly, there it is in the water – the monster! – proof that you’ve been right all along. What do you do? Do you capture that monster fight on video to prove other scientists wrong, and publish the discovery that will make you famous? Or drop down a rope ladder and try to rescue the girl in the water? Desires affect POV – in this case, the desire to succeed in one’s career vs. the desire to help others in danger.

- What if you’re the kid in the food fight who had the mashed potatoes thrown in your face, and you just moved to the U.S. from another country, and you don’t speak English, so kids have been picking on you a lot, and you’re super homesick and sad? Do you fight back because you have HAD ENOUGH, or do you slip away and lock yourself in a bathroom stall for a private cry? Past experiences, and especially past emotions, affect POV.

- What if you’re the cafeteria monitor, and it’s your job to maintain order at lunchtime, but there have been a couple of incidents lately, and you’ve been warned that if you don’t stop fights from breaking out, you could lose your job? Fears affect POV – this case, fear of losing one’s job.

Who we are shapes what we see. Our past

experiences color what we see. And not just see: hear, smell, taste, and touch.

And what emotions bubble to the surface. And how we explain it to ourselves and

others. And what we choose to do about it.

Everyone has their own unique point of view, their own POV.

Twenty-five kids in gym class playing dodgeball will all experience the game

differently. The competitive types will go for the kill every time. Others will

dread the humiliation of being smacked with a ball.

I think we just discovered another thing that affects POV. Personality.

Is there anything that doesn’t affect POV? I wonder. The weather affects how we see the world. A

gloomy day can bring anyone down, and make them pessimistic. Sometimes our health does – for me, things always look

a lot worse when I have a stomach bug! Yuck. Sometimes money affects our POV. If I said to you, “What are you going to do

this Saturday?” you might have some ideas. But if I said, “On Friday you’re

going to win the biggest jackpot in lottery history. What will you do Saturday?”

I suspect that your Saturday plans would change in a massive way. Even your species

affects your point of view. If somebody spilled gravy all over the kitchen

floor, most humans would be annoyed, but most dogs would be overjoyed! Gravy

gravy yum yum.

Point of view

really means how each person experiences

the world and the things, people, and events in it. Clearly, it needed

a shorter name.

|

| The FrankenSquid from "The Trouble With Squids." Splurch Academy book 4. |

I’m not saying there’s no right or wrong. Facts may be correct

or incorrect. Explanations may be wise or foolish. Some choices can be good or

bad, kind or cruel. But understanding point of view helps us see that people

are complicated, that events are complicated, and that before we criticize or

judge another person, we should remember that they see the world differently

than we do. Our way of seeing isn’t the only way.

The best stories are the ones where POV feels very real and

convincing because the author has created a believable life, history, and mind.

As we watch the story unfold, we can say, “I myself would never rob the Crown

Jewels from the Tower of London, but I can see how, for a person like them, in their

situation, it had to be done!” (To save them from being stolen by space pirates.

Obviously.)

Stories are based on the idea that spending time inside

another person’s point of view is fascinating. Getting to know a character is fun.

The better we understand someone’s POV, the more we care about what happens to

them. Understanding POV won’t just make you a better reader or writer. It can

make you a kinder friend and a more understanding human being. That’s the kind

of people our little planet needs. Maybe you’ll think twice before hurling

mashed potatoes. Maybe, instead of filming the sea monster, you’ll drop the

rescue ladder.

Writing Prompts:

- Think of a situation in your life – at school, at home, in the community – where you and another person have a very different point of view about what happened. Write a paragraph describing your point of view. Then write a paragraph from the point of view of the other person, the one who disagrees with you.

- Think of the food fight. Imagine the first person who threw the food, and the person who first had food thrown at them. Who are they? Why did the first one throw the food? How did the second person feel to have food thrown at them? What did they do about it? Write a paragraph from the first kid’s point of view (using the “I” first-person voice, as though you are that kid) to help us understand why they started the food fight. Next write a paragraph from the second kid’s point of view (again using the “I” first-person voice, as though you are the second kid) and tell us about the food fight from their perspective.

- Think of the sea serpent battle. The girl has been rescued; she didn’t die. Phew! Now, pretend you’re a news reporter. Interview each of the people involved: girl in the water, her twin brother in the boat, the scientist in the helicopter, and the guy watching it from a clifftop some distance away. Write the questions you would ask them, and write their answers, showing how they each had a different point of view about the same event. Try to show how things like distance, desires, fears, and relationships affected what they saw and how they felt about it.